Birtherism and the Scholarly Debate over Equiano

How disarming it was in reading the essay “Olaudah Equiano, Written by Himself,” to learn that in the 217 years between the time Equiano (self-published) his Interesting Narrative in 1789 and the publication of Cathy N. Davidson’s essay (by the Duke University Press) in A Forum on Fiction, The Early American Novel, Fall 2006 – Spring 2007, that Olaudah Equiano/Gustavus Vassa continues to face birtherist attacks which threaten to derail his credibility and erase him, like many black writers after him, from the canon, in much the same way that Donald Trump is attempting to erase our first black president’s legacy from U.S. history.

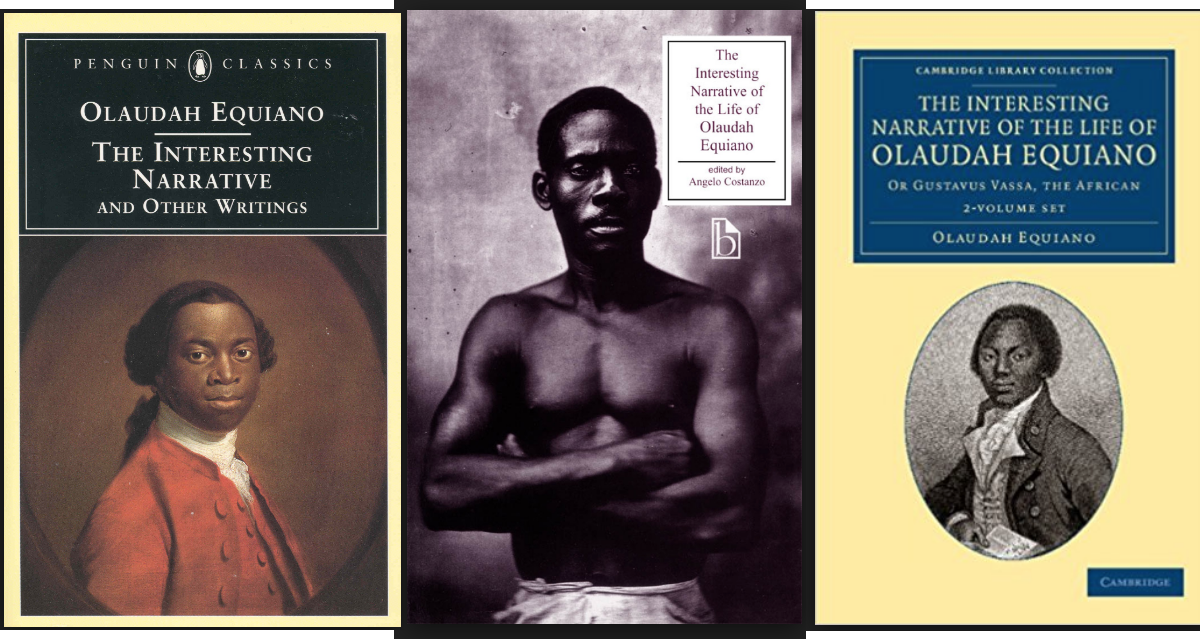

Not only was Olaudah Equiano taken from Africa via the Middle Passage and re-named, stripped of his African (human) identity, but his legitimacy continues — despite undisputable artistic and historical merit of his work — to be questioned by some scholars in the 21st century due to one document: his birth certificate. Further complicating the debate swirling around the Interesting Narrative is the consistent (mis)use of another eighteenth-century black man’s portrait to represent Equiano on the cover of his own memoir. As Davidson put it,

Consider not only the current debate but even the man featured on the cover of both the Penguin Classics Edition of The Interesting Narrative and Vincent Carretta’s Equiano the African. The painting reproduced there is beautiful but the visage of a handsome black man in eighteenth-century British dress belongs to someone else. The back cover of the Penguin edition says it is an anonymous portrait of Equiano although, inside, Carretta notes that the painting was “almost certainly not that of Equiano … [This] is a chilling metaphor for the perils of identify experienced by persons of African descent in Equiano’s era.

The above image shows the Penguin edition’s cover of The Interesting Narrative, followed by the Broadview edition we are currently reading in our Rise of the Novel class, and, finally, by the Oxford Classics cover. The Penguin and Oxford editions’ portraits depict Equiano through another man’s portrait out of convenience, while the Broadview cover makes it explicit to the reader that the face is supposed to be representative of, and not a stand-in for, Equiano/Vassa. This portrait depicts a body enslaved and defined by the shirtless/muscular status, rather than a man dressed in the high fashion of “British” society at that time, another of Equiano’s identities.

It is “chilling” enough that Equiano/Vassa answered to multiple names during his lifetime; even after his fame during the abolitionist movement in Britain, through the literary canon and into the 21st century, the author of The Interesting Narrative continues to be assigned new identities. One need only reference the famous abolitionist graphics depicting slave ships during Equiano’s lifetime for a snapshot of the dehumanizing effects of overlooking the faces and individuality of African bodies, the remnants of which horror echo today.

At a conference in Texas “someone came right out and called Equiano a ‘liar,'” Davidson writes. “Others want to remove the Middle Passage section from textbooks because it isn’t ‘true.'” The Norton Critical Edition of The Interesting Narrative, which I read in an undergraduate course on slavery nearly a decade ago–around the same time as Davidson’s essay’s publication–defines the book not by “Equiano’s” portrait, but through a seascape painting of a slave ship, thus focusing on the journey, rather than the man (albeit that on the rear cover is the same portrait that graces the face of the Penguin edition):

The fact that there is talk of removing Equiano’s compelling Middle Passage section from textbooks — one of the only first- (or even second-) hand accounts of slaves’ experience on a slave ship — and that Equiano, a prominent abolitionist, important, well-connected historical figure of the eighteenth century, and slavery survivor who lived to tell the tale, has been called a “liar” to the extent that Davidson devoted an essay to debunk these claims, reeks of the birtherism that Donald Trump hurled like a chaotic trash heap onto Barack Obama’s campaign for presidency, demanding his birth certificate and challenging his legitimacy by challenging his honesty, the place he was born, and his religion. On The View in 2011 he said: “Why doesn’t he show his birth certificate? There’s something on that birth certificate that he doesn’t like.” Equiano published his birth certificate, ship’s records and a narrative to back it up, and yet his honesty and integrity still is being questioned. On The Laura Ingraham Show in 2011 he said, “He doesn’t have a birth certificate, or if he does, there’s something on that certificate that is very bad for him. Now, somebody told me — and I have no idea if this is bad for him or not, but perhaps it would be — that where it says ‘religion,’ it might have ‘Muslim.’ And if you’re a Muslim, you don’t change your religion, by the way.” This, also chillingly, illustrates why Equiano’s public conversion to Christianity and later to Methodism was necessary especially at that time, to back Equiano’s testimony with “legitimate” Christian/British values, to serve the abolitionist cause.

While some scholars have questioned The Interesting Narrative’s legitimacy due to the birthplace of the author — perhaps — being South Carolina rather than Africa, even to the point of calling the author a “liar,” let us not forget that Equiano was writing in the eighteenth century — the same time period that gave us works of fiction by white men such as Samuel Richardson’s Pamela and Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe, which were published as “biographies” — Crusoe earning Defoe a criminal investigation at that time for being a farce — and which works remain undisputed giants in the literary canon.

The management of the canon — in other words, regulation of what is considered legitimate — is not independent from the times in which we live. Careful examination of language and how it operates with regard to varying authors can help us usher in a future in which birtherist type arguments are analyzed as a rhetoric of the past, preserving the “interesting narratives,” regardless of the author’s birthplace.