Micro, Personal Essays

On Being: In a Pokhara, Nepal Hotel Room

It is not a question of being uptight or not laid back enough on this vacation, in this hotel room. In Wanderlust, Elizabeth Eaves’s world traveler one-upmanship took her to Papua New Guinea on a hike with cannibals; nevertheless her memoir on that experience testifies to that regret toward which hubris was leading her. The woman attuned to her environment does not sleep when, the darkness that surrounds her includes a balcony from which anyone could walk directly into her hotel room, thus avoiding the shards of glass placed menacingly on the outside walls; nevertheless, her fear of the experience remains with her, indivisible from herself forever, branded on that part of her psyche that drives her to fight or flight.

On (My) Self-as-Writer

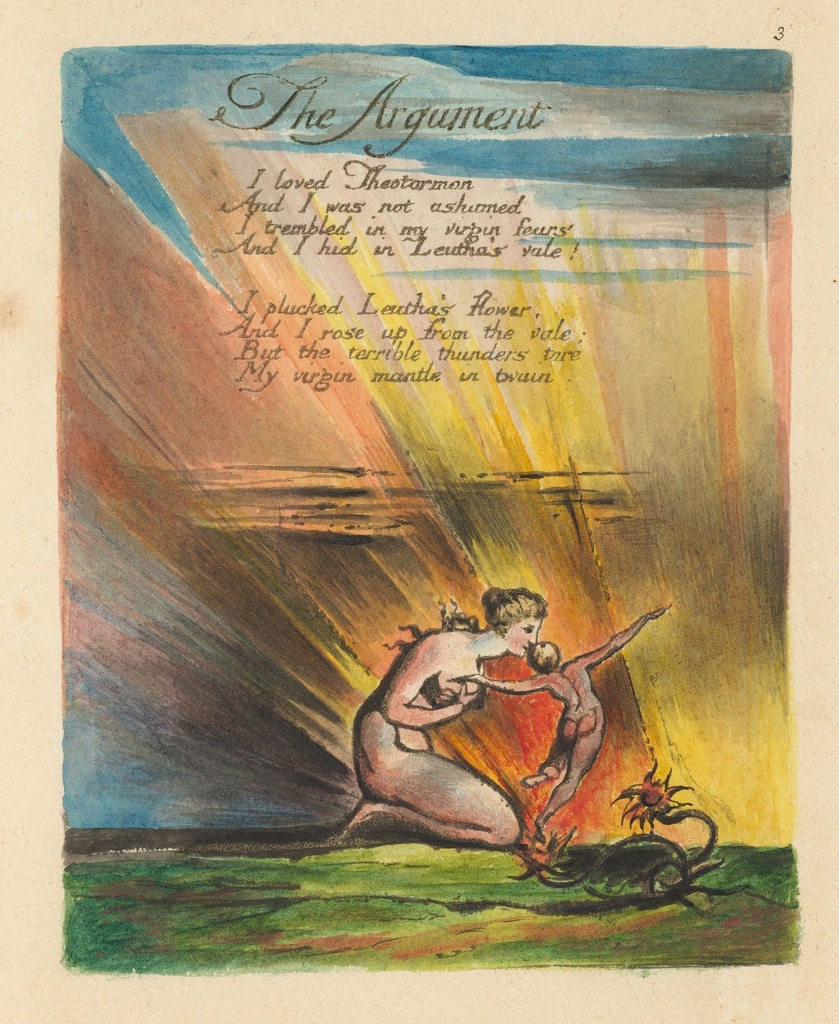

I hesitate to pour the ocean of my life experience into this ice cube tray of a sentence; yet, I posit that Hamlet, the satire of early female novelists like Jane Austen, something concise and timely and imperative of the journalism tradition, my “Irish” Catholic upbringing, and formative career in the U.S. military–and William Blake’s love of difficult texts as in Jerusalem, “Art and Science cannot exist but in minutely organized Particulars, And not in generalizing Demonstrations of the Rational Power: The Infinite alone resides in Definite and Determinate Identity”–have mixed into the internal ocean that is the writer in me today; but I wouldn’t want to generalize or rationalize my own identity.

On Eighteenth-Century Masculinity in my 21st-Century Workplace

When I was in my twenties and talking to my boss at his desk about work, he paused to ask me, “Are you on your period?” I said no. I later rewrote this in my head as a treatise on what year it is, but knew it would backfire. In Evelina: Or, the History of a Young Woman’s Entrance into the World, the title character is constantly reacting or responding to the men around her who either want to sleep with or marry her. She didn’t talk to her boss at his desk about work because women didn’t work a lot in the eighteenth century, so no one asked her about her period. When she was at the theatre with a group of men, though, they asked her what she thought of the main character, then fought with each other over who her favorite character should be. She didn’t interrupt. I resisted eighteenth-century female-authored novels until now due to hard-assery and also subconscious acceptance of the literary canon circa 2007, when my professor was being avant-garde by teaching us Jane Austen in a nineteenth-century lit class.

On “On Morality”

In a northeast suburb of Detroit near the number 3 safest university in the country, tucked into the top corner a 1973 dutch colonial with a fluffy white direwolf/dog, I am writing on Joan Didion’s “On Morality,” and why it’s so good, and the day is dreary. In fact the trees behind the cold window pane are weeping. I cannot veer my mind from some facts: shabby puzzle pieces that are starting to shape, though they are moist, damp, and softened by confusion; frozen and twisted into a distorted picture of perfection. With the detoxifying substances of hot lemon water and Didion’s essay I pour words into the screen. My mind, unlike Didion’s, veers away from the particulars. Sun-doused fragments are hard to look at directly and cast shadows. But I am breaking into the sun and exiting the weeping treescape. So here are some particulars …